This* is an exhibition at Bolton Museum and Art Gallery which lasts until the end of April. It’s solid, unpretentious and has something for everyone, photographically speaking: landscape, cityscape, coast, industry, portraiture and photojournalism. There are some fifty prints in a beautiful mezzanine room toplit through rooflights which you enter by a broad staircase. Fifty is a good number: big enough for variety but small enough for you to give each one some attention. Each image is mounted (sloppily in some cases) and framed, apart from three Leeds City Council Archive prints which are set on foamboard for some reason. The hanging scheme seems to be geographical, starting with the north-east, down the coast, then inland to Yorkshire and over the Pennines to the north-west. This is a bit confusing chronologically but never mind.

The theme, as set out by curator Dr Ian Glover of Bolton University is to examine the photographic representation of the north of England over the century 1890-1990. That’s a big task for fifty photographs. All the names are here: Bill Brandt, Bert Hardy, Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, Martin Parr, Sirrka Lissa Konttinen, Fay Godwin, Humphrey Spender etc. Naturally enough, many, many of the images are old friends, too.

Bill Brandt: Durham Coalminers’ Houses. A well-known image but still carrying a lot of impact.

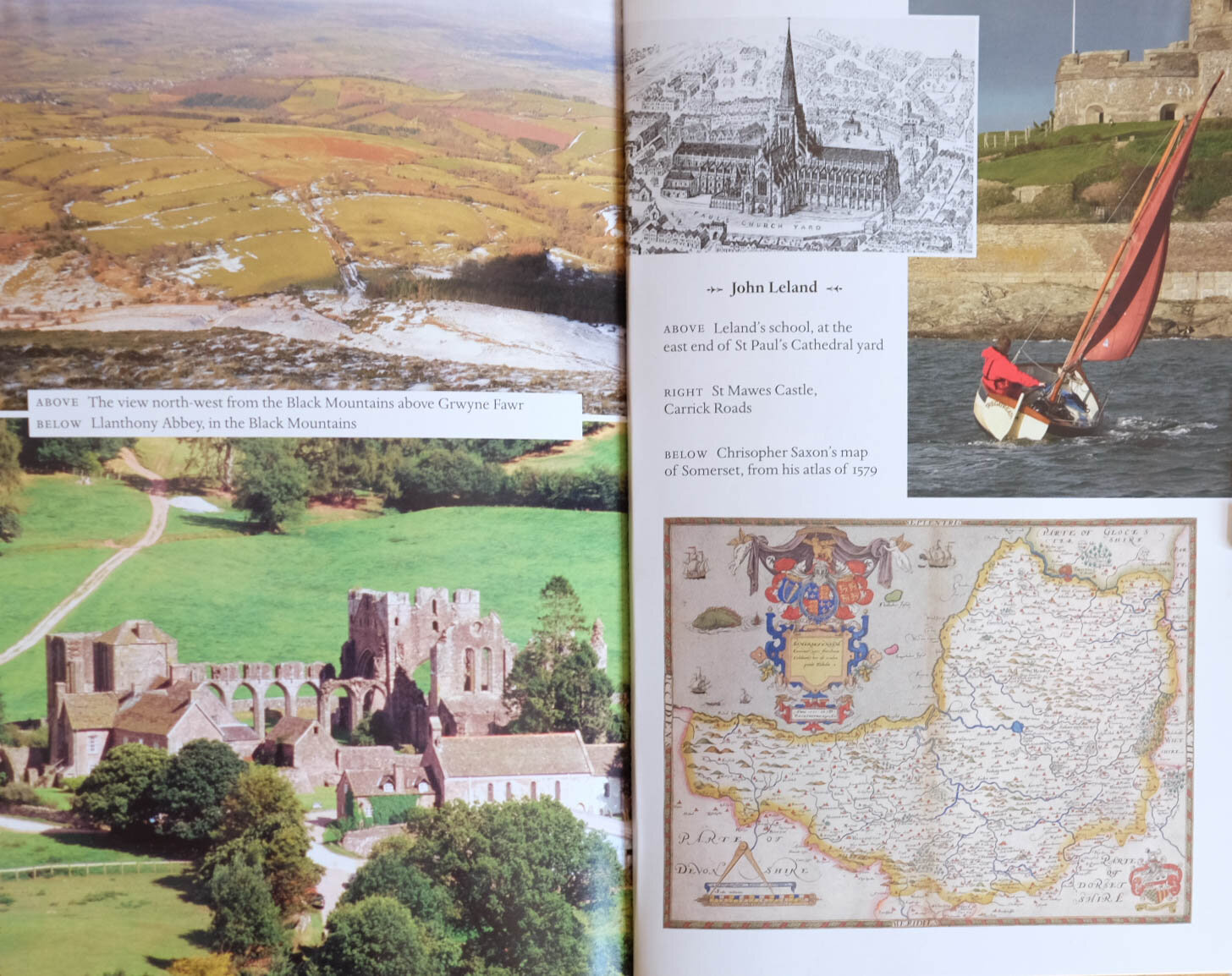

George Melly by Chambré Hardman © National Trust

There are surprising omissions as well: no Peter Mitchell or Don McPhee or Denis Thorpe or Martin Jenkinson or Dorothy Bohm or Shirley Baker. But there were others that I hadn’t seen before like the charming portrait of George Melly to the right which was one of a series of images in the exhibition of the Liverpool middle classes by Edward Chambré Hardman. I had been vaguely aware of Chambré Hardman’s existence from the National Trust stewardship of his old studio in the city. I thought these were a standout of this exhibition (including a rather Hitchcockian Archbishop and a truly surreal-looking portrait of a family named Woolley).

Chronologically the exhibition is tilted quite steeply towards the later 20th century. There are only two photographers representing the first decades: Frank Meadow Sutcliffe and Thomas Shires (new to me; a Victorian photographer of Vanishing Bolton). Nearly all of the rest (bar Hardman and Brandt) are post WW2.

Tow Path, Blackburn, Lancashire, 1984, © Michael Kenna. I love Michael Kenna’s work, too, but I wouldn’t have said it is particularly representative of the north of England. He is known more for his mystical, dreamlike style.

In the booklet accompanying the exhibition the curator says: “I think it is important, at this time in our geographical, historical and demographic development, as we leave the European Union, to examine how the north of England has been represented by photographers.” (I am not entirely sure what he means by geographical development - or indeed demographic development.) That is very ambitious and I can’t say that, for me anyway, any themes emerged from the images themselves or from the rest of the curatorial essay. How was the north in fact photographed – accurately, sympathetically, dramatically, distortedly….? At one end of the scale you have Martin Parr as a kind of Donald McGill of the camera; and at the other you have serious social commentators like Bill Brandt. In between, documentarists, landscapists and social reformers all have their say. But you could get a very similar range of pictures for that period from Clydeside or Wales. The image of the north of England, in the popular imagination anyway, is of coalmines and milltowns strung across a mystical Pennine landscape but I’m not sure that in fact the north hangs together as easily as that. Huge parts of the region were never industrialised and aren’t Pennine: the Lake District, the East Riding, much of the North Riding and Northumberland. There is a significant east/west split as well.* So maybe we could say that photography has played a part in perpetuating a not inaccurate but not very inclusive view of the north. That is perhaps why Hardman’s photographs stand out for me in this exhibition: a smiling bourgeoisie perhaps but an interesting departure from the standard northern themes. (One or two of the photos in the exhibition are of Cheshire, by the by. Cheshire? That’s not The North.)

I thoroughly enjoyed the exhibition. Good size, no nonsense, some knockout photos and a great venue. I followed it with fish and chips at Bolton’s wonderful Olympus Fish and Chip Restaurant with live piano player, too. (Okay, he’d hardly be dead, but you know what I mean.) Then I took a good long walk with the mighty Hasselblad on Smithills Moor above the town.

Does life have any more to offer than a day like this? I think not.

*Photographing The English North 1890-1990: at Bolton Museum, Le Mans Crescent, Bolton, BL1 1SE : 14 March - 26 April 2020. There is nothing on its website but I imagine that the museum is shut now due to virus restrictions. I hop that the exhibition may continue a little beyond its set dates. Photographers exhibited: Bill Brandt, John Bulmer, John Davies, Ian Glover, Fay Godwin, Edward Chambré Hardman, Bert Hardy, Michael Kenna, John Kippin, Sirrka Lissa Konttinen, John Macdonald, Tish Murtha, Martin Parr, Humphrey Spender, Chris Steele-Perkins, John Stoddart, Frank Meadow Sutcliffe.

**See the opening chapter of Peter Ackroyd’s History of England, Volume 1 for some basic facts about that.