“I have never taken any photographs with the intention of publishing them, any more than I have ever made a journey in order to write about it.” There we have Wilfred Thesiger in typically magisterial mode introducing Visions of a Nomad, a 1987 collection of his photographs from East Africa, Arabia and Asia. It may seem an unlikely claim for such a renowned writer but I’m sure that it is honest and it certainly distinguishes him from virtually every current travel writer and photographer who, almost without exception it seems, undertake their travels with publication of books very much in view. It’s a career now, rather than a life.

Thesiger’s own life (1910-2003) is unknowable now. You can readily find the details on the net but it reads almost as Boys’ Own fantasy. His early childhood was spent in the British Legation in Addis Ababa where his father was British Minister. To get to the city at the time you had to go by sea to Djibouti and then undertake a month-long mule ride from the railhead at Dire Dawa – that is how remote the capital was. From there it was prep school, Eton and Oxford and then his first major exploration at the age of 23 to explore the interior of the Danakil country where “three previous expeditions had been exterminated ….. by these tribesmen, who judged each other according to the number of men they had killed and castrated.” It was his firm view that if a journey wasn’t dangerous then there wasn’t much point in undertaking it.

He is probably most remembered for his two perilous crossings of the Empty Quarter, the Rub’ al Khali, in the Arabian peninsula, in what is now Oman and Abu Dhabi. They are recorded in Arabian Sands - which along with The Marsh Arabs is perhaps his best known work. I read those two many years ago and then I recently stumbled across what will doubtless be the definitive biography of him*. Up until that point I hadn’t realised what an accomplished photographer Thesiger was. It is the photography which perhaps distinguishes him from other great adventurers of those times – Philby, T E Lawrence, Livingstone even. He carried a Leica II with a standard 50mm lens from 1934 to 1959 and then swapped to a Leicaflex SLR from then on. (He kept them in a goatskin bag: take that, Billingham.) He had no great interest in photography as a subject but believed (as I do) that once you have learnt to expose and focus properly, the sense of composition is instinctive: either you have it or you haven’t.

What is interesting about the photographs - apart from their content, of course - is that the style tells us probably as much about the photographer as about the subject. They are simple, austere and straightforward. They are well-framed, steady and unpretentious. But there is an unmistakable air of the butterfly collector and his specimens.

A Junuba, from Southern Oman. “…these striking people, knowing nothing about photography, adopted no self-conscious poses. …….. I took many photographs of relaxed and graceful tribesmen. Now, with the influx of tourists, all anxious to get photos, they have learnt to pose and demand money…..” (Many of his portraits are shot upwards like this so that the sky provides a plain background and the subject assumes a slightly heroic aspect.)

Young girls of the Yam tribe, near Najran in southwestern Saudi Arabia. “I tried to catch the turn or lift of a head, the set of the mouth, the reflection in the eyes and the combination of highlights and shadow on the face and by doing so to get an effective picture.”

“Launching a small dhow for the sheikhs to sail me around the islands on my arrival in Abu Dhabi in 1948, after my second crossing of the Empty Quarter.” I bet many a travel writer would give their eye teeth to be able to toss off a sentence like that nowadays.

An elderly man in Ladakh. “I have never taken a colour photograph and nor have I ever felt the urge to do so…….I am convinced that black and white photography affords a wider and more interesting scope than colour…… With black and white film, each subject offers its own variety of possibilities, according to the use made by the photographer of light and shade.”

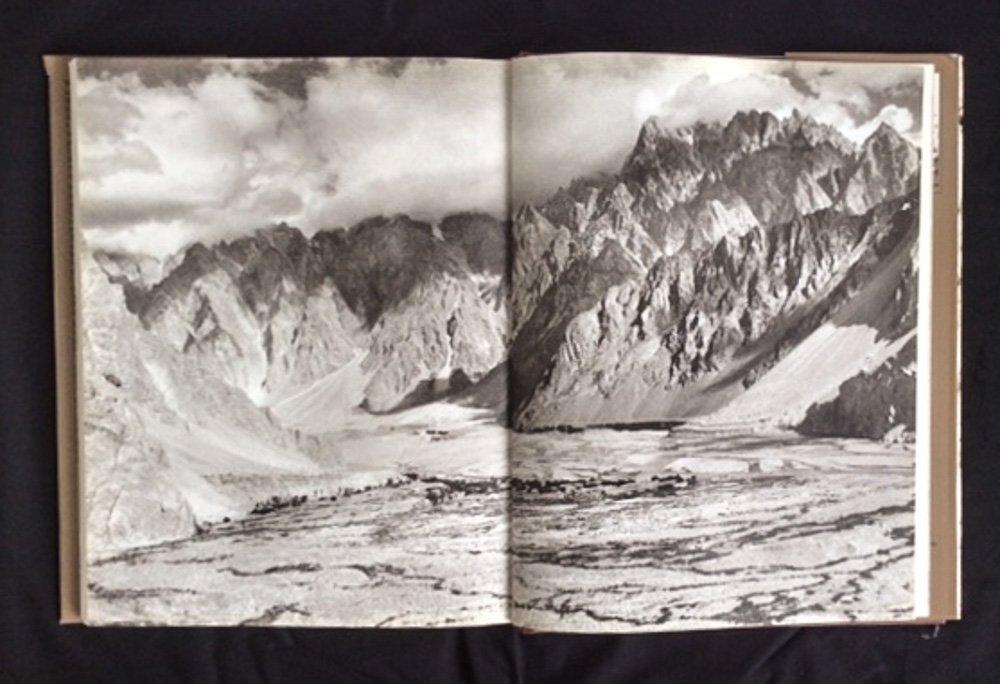

In the Karakorams of Pakistan, north of Baltit, capital of Hunza. “Among the landscapes which I saw as I passed slowly by - on foot, not fleetingly glimpsed from a car - I remember in particular a scene in the Karakorams with villages in a valley dwarfed by towering mountains. For me this picture symbolises that mountain journey, and always there was the interest in seeing how a landsape could be improved by altering the foreground, sometimes by only a short distance.”

You simply don’t see this kind of photography anymore. Thesiger says: “When I browse among my sixty-five albums of these selected photographs, my most cherished possession, I live once more in a vanished world.” That world has vanished, it is true, but so has the world which was on his side of the camera - his world view, that is. He says of the Bedu that they “had no conception of a world other than their own” but the Eton and Oxford educated product of the British upper classes seems to see no irony in that statement. They are his specimens but by writing his books and publishing his photographs he too became a specimen. It’s curious but the images in Visions of a Nomad, excellent, interesting and absorbing as they are, also show that photography is a means of record in more ways than one.

* Thesiger by Michael Asher: Penguin Books, 1994.

All photos taken on my iphone. The originals and text in Visions of a Nomad were © Wilfred Thesiger 1987.