Little, Brown and Co, 1996

Go on. Who would you say was the most popular photographer of the 20th century? Not based on statistical evidence of sales or exhibitions or whatever – just straight out profile in the popular imagination. I’d say it has to be Ansel Adams (1902-1984). Cartier-Bresson might give him a run for his money but in the end I think the Frenchman is more admired by other photographers while Adams is more popular at large.

Having just read his autobiography, which I picked up locally secondhand, I can see that his personality might have had something to do with it. He comes over as a very attractive, affable, chatty, kind of chap – very opinionated but with tremendous energy and enthusiasm. He loved a drink and good company. He didn’t take any prisoners, mind you. Here he is in a letter to William Mortenson dismissing Pictorialist photography and celebrating Realism: “How soon photography achieves the position of a great social and aesthetic instrument of expression depends on how soon you and your co-workers of shallow vision negotiate oblivion.” Boof!

You might now see him as part of the Romantic movement which in photography died out as a serious form in the 1970s, post-Minor White. I’ve never seen any of his prints in the flesh but even on screen you can see how he managed to squeeze every drop of tonality out of his negatives. I guess it would have been pretty extreme – and technically difficult – at the time but in these days of Photoshop and High Dynamic Range they look pretty middle of the road, tonally speaking. You can see a good range of his images here. They are striking or overwrought depending on your taste.

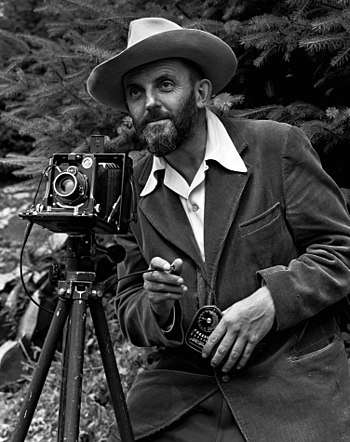

Ansel in the 1950s (by J Malcolm Greany) looking rather dapper, light meter at the ready.

His bottom line, always and ever, is that photography is a creative art and that to see or use it as anything else sells it short – though he himself of course had to take on commercial commissions to survive. He didn’t get on with Edward Steichen who in the late 1940s sidelined Ansel’s friend Beaumont Newhall and became Director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. “Everything we feared” writes Ansel to Beaumont, “the complete engulfing of photography as you and I see it ….into a vast picture archive.”

Steichen’s hugely popular Family Of Man exhibition – whose aim was to show “the essential oneness of mankind” – was the last straw for Ansel (even though one of his own photos was in it!) He thought it was more suited to the United Nations than to MoMA.

That jibe about “a vast picture archive” went to the heart of his philosophy. For him it wasn’t so much about the subject of your photograph as the way you produced it and the communication of feeling that represented. You had to control the whole process from visualising the photograph to developing the negative, choosing the paper, making the print and displaying it. That could be a long process and sometimes he took several weeks working on a print to get it just right – and then over the years he would develop that further.

You might say now that for many, it is precisely the subject of a photograph rather than image quality which is its main interest. That’s why The Family of Man was so popular. But maybe Ansel had a point, too, because you could also say that there are limited subjects but limitless ways to capture them photographically.

Environmentalist, pianist, inveterate letter-writer and very liberal in many of his social views, Ansel Adam’s autobiography makes a good (if meandering) read. You go back to your own photography with renewed vigour. Enthusiasm is such an attractive quality in a person.