What’s hard to find these days is something that’s hard to find. I think it was Alan Bennett who wrote that and if he didn’t he certainly should have done. Everything is so over-marketed. So when I spotted two little photo exhibitions locally putting their hands up at the back of the class, so to speak, I made a point of going to see them. They were Bury Art Museum‘s A Celebration of Life in the North 1970’s – 1980’s; and Capturing the Modern Backdrop: Shirley Baker Photographing Salford at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford. Ostensibly they had much the same focus but but turned out to counterpoint one another very interestingly.

So first to Bury on Manchester’s wonderful tram system. I love these trams and especially their distinctive toot-toot: they make me feel so cosmopolitan, so – dare I say it – European. The Museum is nobbut a cockstride from the tram terminus and has a lovely atmosphere. It’s local without being parochial, has a great café, and the person on reception has a beautiful Lancashire accent. Upstairs British Culture Archive has selected 31 photographs in its collection from four photographers: Don Tonge, Chris Hunt, Luis Bustamente and Thomas Blower as, I guess, a representative sample of late 20th century images of northern England.

I contacted both British Culture Archive and Bury Museum for permission to show one or two photos from the show but haven’t been able to get a reply out of them. So my iphone shot of Don Tonge’s ‘Newspaper Seller, Manchester City Centre 1970s’ will have to do for the moment. Newspaper sellers have disappeared from the streets of course now and so have their “Late Night Final!” cries.

The British Culture Archive was founded by Paul Wright in 2017 “to document, highlight and preserve the changes in British culture and society through documentary photography”. That’s a big project and 31 photographs can only give a flavour of the range that you can find on the BCA website (link above). I do wonder, incidentally, if archives like these are going to take over from social history books as a record of people and place. Oral history would be a natural partner for these visual records and together the two might give a fuller narrative than a third-person historical account can do.

The exhibition had side displays of books, records, magazines and other memorabilia from the 70s and 80s but virtually no curatorial comment. Although I often find curators’ remarks distracting, in this case I missed them a bit. Why these pictures, I wondered, and why now? And precisely what did they illustrate about 1970s and 1980s Northern England? Also: just what is so northern about them - delightful though they are? After all, there are very similar series from other parts of the country: Roger Mayne’s Southam Street for example; or Oscar Marzaroli’s Glasgow archive; or Vanley Burke in Birmingham. Then there all the Cafe Royal books. The UK is a small country and things don’t vary as much from corner to corner as we sometimes imagine.

Nonetheless it is hard to resist the allure of this saunter down memory lane. The photos are charming, the display unfussy and there is plenty to delight the eye and interest the mind.

From Bury I caught a tram back to Victoria Station and then walked up into Salford which took a good 45 minutes or so because I wanted to go across Blackfriars Street and then along Chapel Street which is a small but atmospheric part of Manchester where to your left you can see the high-rise future coming into being while on the right the low-rise past disappears. I eventually staggered into the cafe in Salford Museum and Art Gallery to ask myself the question that I always ask there: how can such a beautiful café space have such a dreadful menu? The café is light, spacious and has a fabulous bay window looking out over Peel Park. It’s really lovely. The best I could find on the menu was beans of toast but it was catering pack beans and possibly the worst bread I have ever tasted.

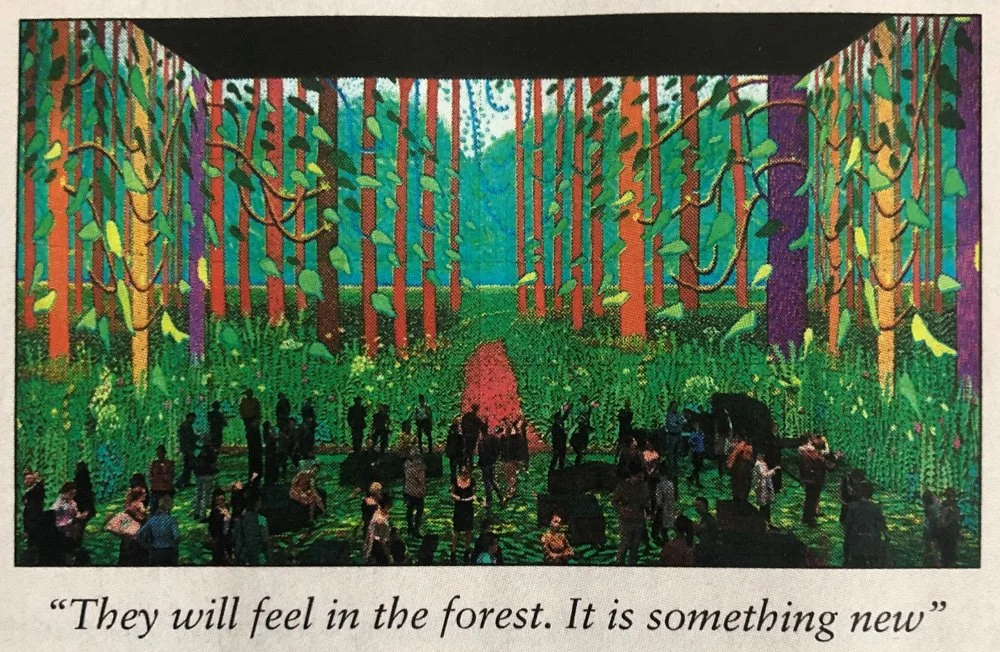

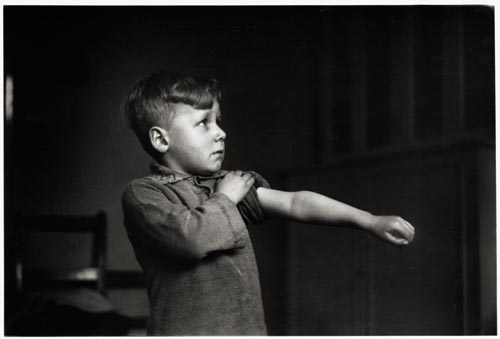

Over the road then and into the Working Class Movement Library – an ex-nurses’ home which houses a collection first put together by Edmund and Ruth Frow in the 1950s and now numbering around 33,000 books. The Shirley Baker exhibition was in one room and comprised 15 photographs (in the ubiquitous black frame, I am afraid, as were the ones in Bury). A casual glance might have suggested that the photos were much the same as those in Bury but an article in a local history magazine displayed on a nearby table and a reinspection of the photos brought out some deeper features of the display. Essentially, what the article said was that Shirley Baker was not simply a chronicler of the streets of Salford but had a very disciplined focus on the process of history – on the changing visual aspect of the city and its effect on its people. The streetlife for example of children’s play and adult conversation which disappears as the tower blocks rise and the back to backs are demolished. Looking round again I realised how accurate that comment was. This, for example……

…gives way to this……

I couldn’t get a reply out of The Working Class Movement Library either. Both images © Estate of Shirley Baker

There were also interesting contemporaneous press reports and inquiries into the dire mismanagement of housing provision in the city. Plus ça change, eh?

From there I got the bus back down into Manchester and the tram home. It was a Grand Day Out: some fine photos; interesting ideas to chew over after the visit; and a feeling that I had unearthed something for myself rather than having been the target of gallery marketing departments.

The Bury Art Museum exhibition continues until 18 May and the Shirley Baker exhibition until 21 April.