When I was racing around on motorbikes – which I did for several decades – I had some big ones: 1000 cc BMWs and Moto Guzzis in particular. Bit by bit however I began to realise that it was the smaller ones which were the most fun. I rebuilt a dead 350cc Moto Morini once and rode it for several years finding out just what it was capable of as a tourer and roadster and daily commuter and really enjoyed it. It was economical to run, went like the clappers, could, with ingenuity, take all my camping gear; and if it fell over I could pick it up with one hand.

Image from the Hasselblad company’s website

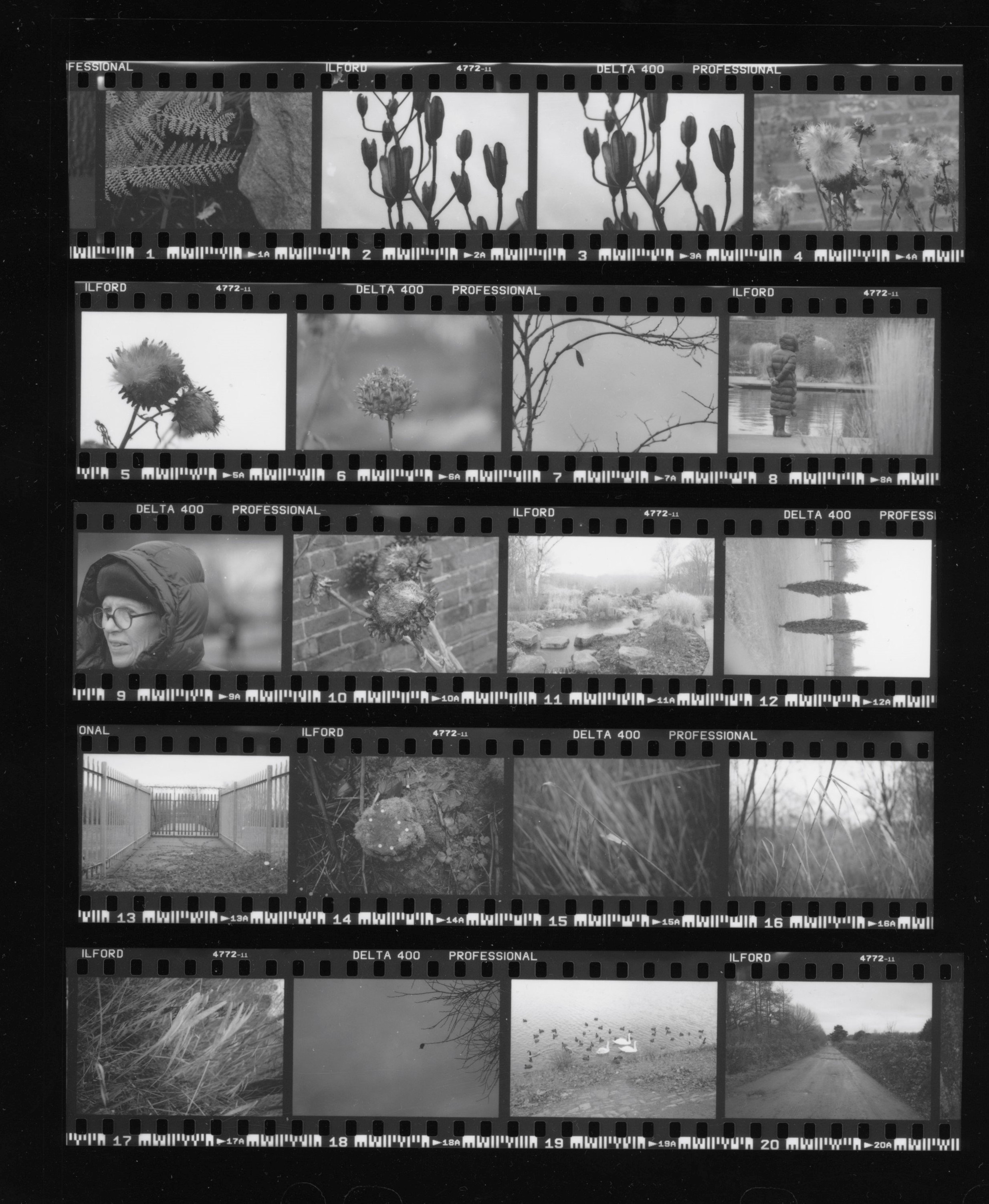

For the past few years I have owned a Hasselblad 500CM and a 35mm Olympus OM. I can’t help feeling that the former is the photographic equivalent of the BMWs and Guzzis and the latter is more like the Morini. Which is why I finally decided to sell the Hasselblad.

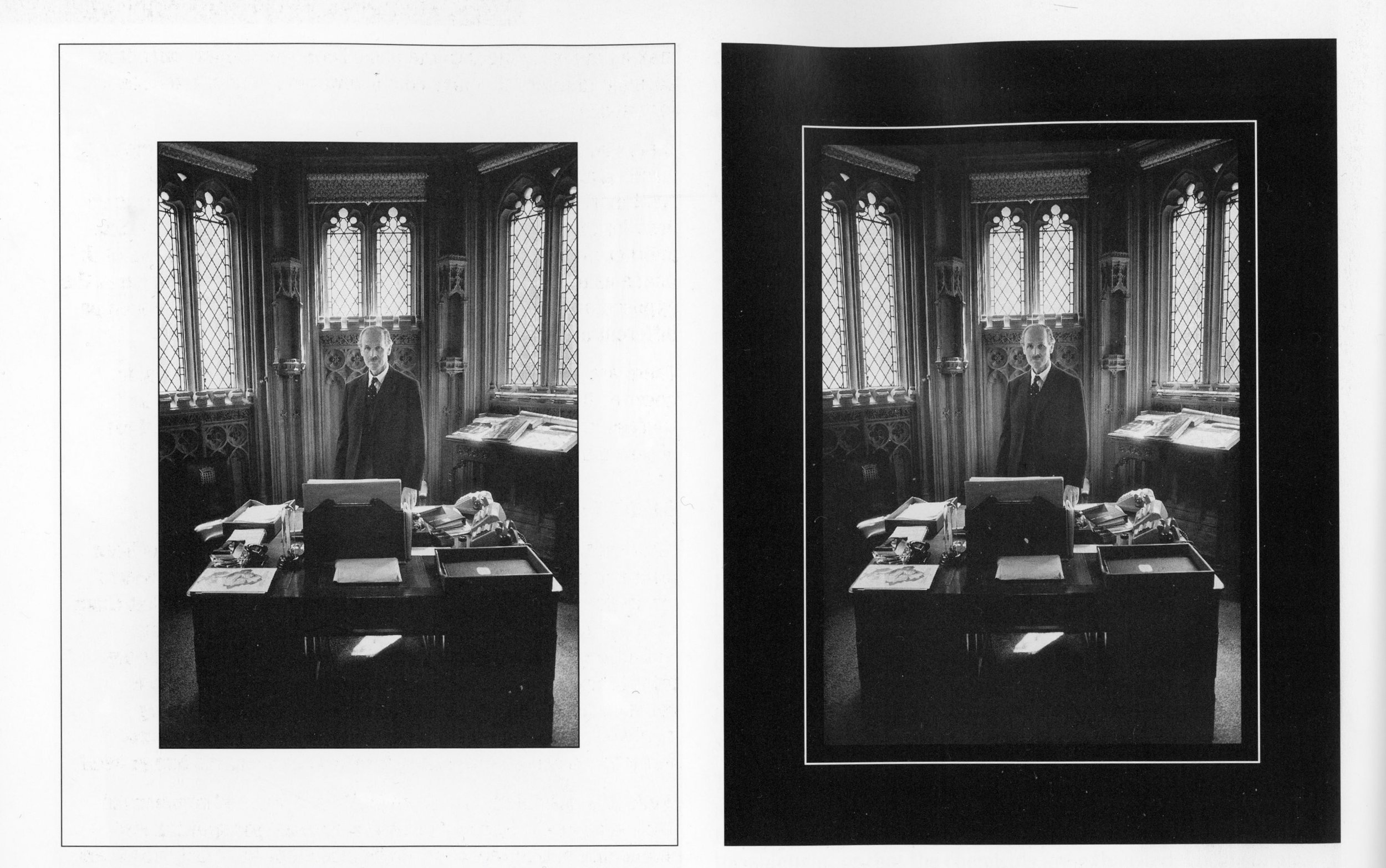

There is an interesting article about the Hasselblad as a day-to-day camera here. My experience was that it was a fine camera with great lenses but all in all a bit of a faff for the kind of thing that I do – which is basically to photograph life as I find it. It was heavy (especially with an extra lens or two); like all MF had a desperately shallow depth of field; took an eternity to focus; I was forever forgetting to take out the dark slide before I pressed the shutter button; and I didn’t really like walking around with such an expensive piece of kit hanging from my shoulder. It’s true that the results were often very pleasing but they were rarely spontaneous. I’m not a collector and I don’t like cameras hanging around on the shelf gathering dust so it had to go.

I do still have a Rolleicord but I wonder sometimes if MF might be approaching its sell-buy date. 35mm is nimbler, cheaper, simpler and more popular. And all the advantages of MF can be improved upon by going to large-format which seems to be gaining adherents all the time. So MF is squeezed in the middle. Both Kodak and Lomography dropped the price of 120 film recently and I do wonder a bit about a drop in demand.

The question of image quality always comes up when MF and 35mm are seen as being in contention. IQ is an ill-defined concept but I do think that you can often get more atmosphere out of the smaller format. It may not be quite as sharp in larger prints but that leaves it with a power of suggestion that can be a great asset.

I enjoy just using the one camera and a couple of lenses. I can explore what in motorcycling is known as the performance envelope and become really familiar with the one machine. It’s remarkable what this discipline reveals: hidden characteristics begin to emerge over the months and years and the one piece of kit becomes truly familiar. It’s well worth it.