Can The Bicycle Kick Be A Work Of Art?

Photograph copyright Luiz Paulo Machado

For those interested in the uses to which photography may be put, the current exhibition Pele: Art, Life, Football at the National Football Museum is fascinating. It is a celebration of the career of the Brazilian footballer, Pele, through a variety of media which straddle the worlds of art and sport. On the artistic side there are about twenty-five paintings, mixed media collages, and prints on canvas and linen – nearly all based (I’m guessing) on photographic originals. Then there are the non-artistic exhibits such as medals, trophies, newsreel footage and so on which may perhaps be of more interest to the football fan. So it is an exhibition (art) within an exhibition (football). Or that is the way it seems at the NFM. Perhaps when it was first shown in a London gallery in 2015 it looked like the reverse.

Then there are the photographs – some fifteen silver gelatin and giclee prints. Which side of the sport/art line do they fall? To my mind there is a slightly uneasy tussle going on here. Downstairs at the NFM the celebration of both sporting achievement and personalities is strictly digital through wall-mounted screens in grids that zoom in on particular stars and show them both in stills and footage and include text of quotes lionising the individual footballer within the display. These are classic digital displays splicing data bundles of text, collage, and moving and still image to emphasise athleticism and reputation.

But upstairs in the Pele exhibition motion picture is separated entirely from still image and text is separate again. The moving pictures are placed firmly in the sporting display category and physically separated in a small cinema mock-up at one end of the exhibition.

The still photographs are interspersed with the other artwork but they stand a little awkwardly there. They are displayed in the same way – mounted and framed and hung on the wall with accompanying title and text about the print. They can certainly hold their own in simple terms of display since they are as big and impressive as the artworks (although, surprisingly, almost none of them are credited to a named photographer). And they hold their own in price as well, coming in at around £3-5000 which is in the same range as their non-photographic neighbours.

But that is not the point. Seeing these old news photographs here in this way is more like seeing your next door neighbour at a celebrity event in the pages of Vogue magazine. They don’t look comfortable and they don’t have their normal clothes on. They are drinking cocktails when they should really be leaning against the bar with a pint and a roll-up. They are out of place – not because they are photographs but because of the ambiguity of the context. After all, given the age of some of these images, it is quite possible that fish and chips were once eaten off them. The bicycle kick motif that runs through several of the artworks is pretty well known but you really don’t have to pay that much for it. You could once get it on your mastercard if you wanted and maybe you still can.

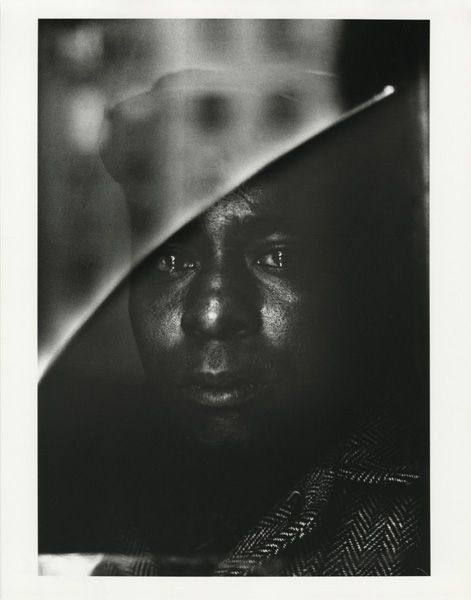

Pele was perhaps the first footballer – even before George Best – to be made a superstar through photographic imagery. The exhibition itself makes this clear The earlier photography is black and white from the era before anyone had ever thought of football as “the beautiful game”. These early images don’t support that contention of beauty. The camera angles are a bit too low, the images too grainy and the action too jerky. But you can see how the advent of colour and technological improvement in lenses and cameras changed the game’s aesthetic. There is one photograph on display entitled “Unstoppable!” which shows Pele in front of an array of defenders apparently packed into a tiny space in an unavailing attempt to stop him. My guess is that the defenders were in fact more spaced out than that and probably watching other attacking players too but the telephoto lens has drawn them all into that tiny area which makes it look as though they are all needed to stop one man – Pele. Similarly the film footage goes from one or two touchline cameras to higher, multi-camera views which give a much better idea of a game’s flow and strategy and sets up hero roles within that.

So for the student of photographic culture the exhibition may lead to two conclusions. The first is that the status of photography out there in the wider world remains as uncertain as ever: from The Sporting Pink to chip wrapping to credit card to gallery wall, it can be whatever you want it to be - forgotten image, sporting memorabilia or work of art. And secondly it shows how developing photographic technology creates its own truth. The Saturday afternoon working –class relaxation of the first half of the twentieth century, has become The Beautiful Game of the century’s later years. The ‘muddied oafs’ of those early years, all dubbin and centre-partings, have become technicolor gods whose sporting achievements are embedded in endless data bundles served up for the adoration of mortals. The king is dead, long live the king!

(Pele: Art, Life, Football continues until 4 March 2018 at the National Football Museum, Urbis Building, Cathedral Gardens, Manchester, M4 3BG)