Language is a wonderful thing. One theory is that it came into existence in early hominoid social groups as a more efficient means of communication than grooming. I’ve no idea what the evidence is for that but it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see how important language is in forming relationships and creating status, just as grooming may once have been. Then what started out as a few grunts and groans ended up as War and Peace, or Hamlet. Presumably, words just started pouring out, as they still do. New ones turn up out of nowhere to fulfil a need and disused ones die off.

All the same, it’s not uncommon these days to find someone conjecturing that images will soon usurp language as our primary form of communication. I think that is pretty unlikely: images cannot make statements and they know nothing of particles such as ‘not’, ‘when’ and ‘if’ and so cannot contain negatives, time, or conditionality. They can of course arouse emotion - but but they cannot express it. A photograph of an angry person does not tell you whether the photographer was angry. On the other hand, if I read the words of someone who is very angry I can easily surmise that they are angry (though I in turn may not be).

So the dividing line between words and images is pretty clear. And when you put the two together you can get some powerful results - advertising and propaganda being two examples. But if you don’t really get it, then the result can be the sort of confusion I noticed in a newspaper piece recently.

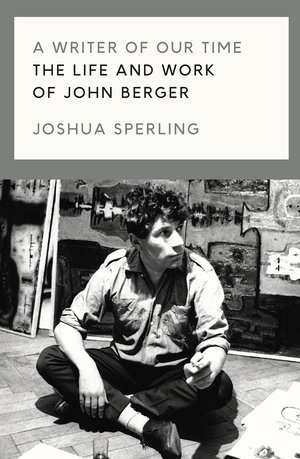

Every week in the Guardian there is a Q and A session with a writer in which more or less the same questions are asked: the book that changed me; the last book that made me cry; the book I wished I’d written; and so on. The writers are generally pretty knowledgeable and, as you’d expect, well-read. A couple of weeks ago the interviewee was Vick Hope, a broadcaster and writer who this year is one of the judges for the Women’s Prize for fiction. Her answers showed her also to be intelligent, well-read and knowledgeable. The accompanying picture though baffled me. To get the combined effect you can find them both on the Guardian’s website here: you need to see the two together to get the full effect and there is too much to reproduce here. (The quotation under the photo on the website didn’t feature in the hard copy, by the way.)

If you turned the magazine page round and squinted hard at the credits you found that the photo had in fact been shot for an airline company. Vick Hope is beautifully turned out in an off-the-shoulder evening dress of some sort and she is wearing drop earrings and full make-up. The foliage background is a bit strange but you can see how it might possibly make sense if you were promoting some sort of international travel. Her stance is neutral except for the positioning of the right arm, which is rather model-like, and the curious upward tilt of the hand at the hip which has twisted the whole of the forearm up to the elbow and looks a bit uncomfortable. What I can’t work out though is the connection between this photograph and the words below it about Vick Hope’s tastes in literature. The two are miles apart – they aren’t even within waving distance.

This is not to say that a woman who dresses in a glamorous evening dress and drop earrings cannot be a perfectly serious literary figure. Obviously, she can. But for the purposes of the Guardian literary pages the picture adds nothing to the Q and A session. There is no mention in the text of travel, parties, fashion, or even an interest in background hedgerows. Text and image are about two completely different things and you wonder why on earth they were ever paired together like this. The photo does not supplement the text. It illustrates nothing. And the text tells us nothing about the photo.

This is not uncommon. There will be a press article about someone whose appearance is of little relevance to its contents. Yet the inevitable photograph appears next to the text, floating around like an unmoored barrage balloon. It makes me think of C S Lewis and his famous lecture on The Two Cultures. He argued that the many contemporary ills (this was 60 years ago) could be traced to the gap between the two worlds of science and the humanities. Scientists knew little of the humanities and humanists knew little of science. The same is true now of the visual world and the verbal world. Visual literacy is for specialists - and those specialists do not always have the best of intentions.

This is the great unexplored area. Words are powerful. Text is powerful. Working together they are unstoppable; yet we are still at the grunt and groan stage in analysing the text/image relationship. The ideas have not yet emerged which could throw a bridge across the waters dividing the two.